I’m glad to belong to the generation that witnessed the dawn of the digital age and its impact on our day-to-day lives. Younger generations have no more clear picture of what life was like before computers than I can conceive of what it was like when horses were the primary mode of transportation.

I’d never want to go back to manual typewriters, pay phones, stopping at gas stations to ask for directions, and loading film into cameras. But I’m not much interested in going forward either. I have all the personal devices and apps I need. More in fact.

Not in the photo of my digital world is the Amazon Dot, “Alexa.” I bought it for my centenarian friend, Elizabeth, who could no longer see well enough to operate a CD player. I figured she could use voice commands to play music. Sadly, she died before I got it set up. I brought it home and use it as a timer or to stream music. I continually receive emails detailing all the wonderful things I could be doing with Alexa. My response is, “Who needs it?”

That was my response when tablets arrived on the scene. Then I attended a recital featuring a pianist who was reading his music on an iPad and turning pages with a foot pedal. Instantly I realized, “I need that!”

When Facebook arrived on the scene, I wondered “Who needs it?” Apparently 2.7 billion people.

Before moving into my smaller house I measured to make sure there’d be room for a small grand piano. I bought a high-end keyboard, thinking it would serve me temporarily until I found the right acoustic grand. That was five years ago. If a grand piano were to land in my lap (unfortunate metaphor—that would hurt!), I’d make room for it. But I still wouldn’t give up the keyboard and its varied sounds, rhythmic functions, recording ability. I need those.

Innovation continues to happen, and obsolescence is an essential part of digital marketing. Whatever you just bought is obsolete the day after the Amazon drone delivers it. A lot of people worry about the impact of Artificial Intelligence. That doesn’t worry me as much as human intelligence, or the lack thereof. Self-driving cars are predicted to take over the roads just around the time when I should give up driving. I’m sure I’ll need one of those.

(To celebrate my 75th birthday this month, I’m posting daily stories about the stuff I’ve acquired over a lifetime and can’t let go of. I invite you to consider the stories attached to the stuff you treasure—maybe even share them.)

I’d intended to burn them when I moved and down-sized. Three boxes of letters, two large ones containing John’s letters to me, and one small box of my letters to him. He could always out-write me. He’d sit at the typewriter, later computer, and punch those keys with the passionate fury of Horowitz playing Chopin.

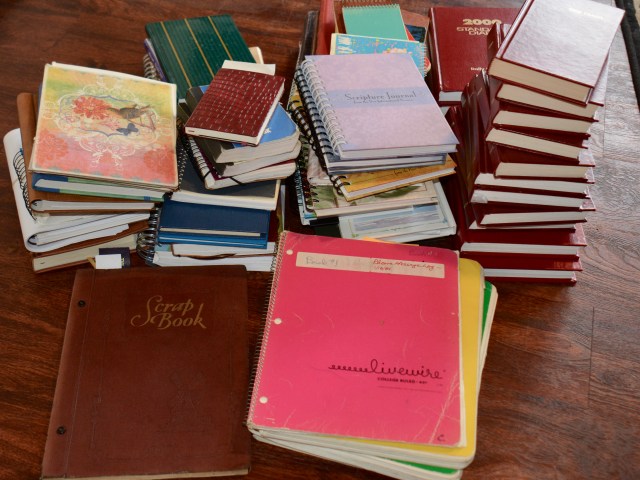

I’d intended to burn them when I moved and down-sized. Three boxes of letters, two large ones containing John’s letters to me, and one small box of my letters to him. He could always out-write me. He’d sit at the typewriter, later computer, and punch those keys with the passionate fury of Horowitz playing Chopin. These are my “someday” projects. When you turn seventy-five, you begin to realize that your opportunities to find that “someday” are steadily diminishing. This odd assortment of notebooks, journals, and scrapbooks are the private musings of four people: my father, mother, husband, and me.

These are my “someday” projects. When you turn seventy-five, you begin to realize that your opportunities to find that “someday” are steadily diminishing. This odd assortment of notebooks, journals, and scrapbooks are the private musings of four people: my father, mother, husband, and me.  If Okanogan County were to elect an official county bird, I would vote for the quail. I understand this quirky little bird is not native to the county, but then neither am I. With its bouncy topknot, woo-hoo call, and clumsy strut the beloved quail is frequently found in the work of local artists. Some of my favorite quail representations are in the pottery of the late Everett Lynch (1898-1988).

If Okanogan County were to elect an official county bird, I would vote for the quail. I understand this quirky little bird is not native to the county, but then neither am I. With its bouncy topknot, woo-hoo call, and clumsy strut the beloved quail is frequently found in the work of local artists. Some of my favorite quail representations are in the pottery of the late Everett Lynch (1898-1988).

Last night, on the eve of a rainy Memorial Day weekend, I indulged myself with a seventy-five-year-old’s version of a campfire. Certainly there are more attractive chimineas than this battered, rusted Coleman so-called fire pit, but the brand name alone makes me nostalgic.

Last night, on the eve of a rainy Memorial Day weekend, I indulged myself with a seventy-five-year-old’s version of a campfire. Certainly there are more attractive chimineas than this battered, rusted Coleman so-called fire pit, but the brand name alone makes me nostalgic.

There’s a myth about downsizing that goes something like, “Once you get rid of this stuff, you’ll never miss it.” So not true. Many times over the past five years, since I moved from an unreasonably larger home to a reasonably smaller one, I’ve had this inner dialogue:

There’s a myth about downsizing that goes something like, “Once you get rid of this stuff, you’ll never miss it.” So not true. Many times over the past five years, since I moved from an unreasonably larger home to a reasonably smaller one, I’ve had this inner dialogue:

You must be logged in to post a comment.