Late at night, lost in the cavernous and empty Seattle Convention Center parking garage, I realized the truth of an old adage: You can’t go home again. This was a while ago, before we had smart phones to tell us where we’d left our cars. Even when I finally located the car, I couldn’t find an exit that wasn’t blocked by an unyielding mechanical gate.

Seattle once was MY city, where I’d studied, worked, romanced, played, and prayed. Except I never lived within Seattle city limits but on Vashon Island, which was then an affordable fifteen-minute ferry ride across Puget Sound. My life style would be impossible today. It was the ’70s, before Microsoft and Amazon. I owned a ramshackle house with a grandiose view of the sound, both Olympic and Cascade mountain ranges, and the Seattle skyline. I’d walk to the ferry and commute to class or job or whatever.

My nostalgia was provoked this week by the opening of a new, two billion dollar Seattle convention center. It’s pretty much next door to the “old” center, which opened in 1988, was doubled in size by 2001, and will continue to operate. The hope is that new center will reverse the dismaying decline of the downtown core. Its event and meeting spaces equal ten football fields. That doesn’t include the public parking garage, into which I surely won’t venture. I never figured out the old one.

I once was a master of Seattle navigation, knew the back streets, shortcuts, escape routes. I learned from one of the best. As an Associated Press editor, I rode along with an AP photographer who I swear invented alleys and byways that didn’t exist for regular drivers.

Even though I was working for the world’s largest news gathering organization, I didn’t want to go anywhere else in the world. I turned down any and all promotions that would require moving. I smiled as I read reports from along the Iditarod trail, written by a colleague who accepted the job in Alaska that I’d declined. Didn’t matter that I was working the crummy overnight shift in Seattle. I could watch the Space Needle’s glittering lights through the office window.

Slowly, though, the idyll was fading. Commuting, even by ferry, was becoming unreasonable as gridlock strangled the city. Eventually I got an offer I couldn’t refuse. It came from the owner of a weekly newspaper in a gritty little eastern Washington town. He was striving for five thousand paid circulation and figured I could help get him there. It was a package deal: a significant cut in pay, a marriage proposal, and a pledge that we’d visit Seattle monthly for my vital infusion of urban energy — theaters, restaurants, and salt air.

In 1994 we dallied for four months in the city following my husband’s paralyzing stroke. John was a rehab patient at the University of Washington Medical Center. I lived in an aging residential hotel on Capitol Hill, cheering him on, terrified of the future, seeking solace in all that urban energy.

Even after John’s death in 2007, I’ve surprised myself by returning to Seattle only rarely. Certain landmarks are still there. No one’s going to move Mount Rainier. They did move the bus depot without telling me. A couple years ago, thinking about that gridlock, I parked my car in Wenatchee and rode the bus the remaining hundred and fifty miles to Seattle. I was stunned to disembark in a strange area on a rainy night, multiple blocks from the hotel that I’d thought would be just a short walk away.

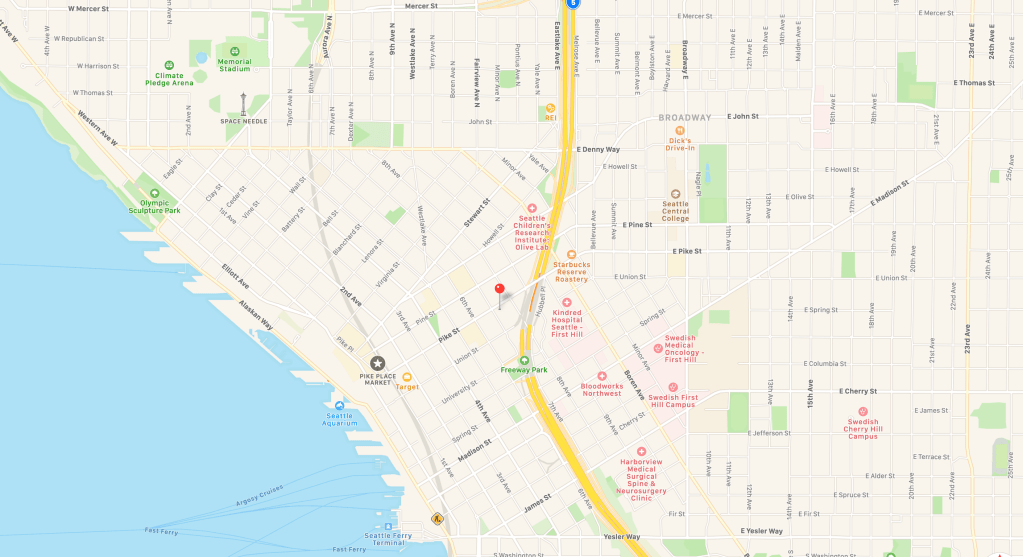

My long-ago favorite restaurants, hotels, hangouts are either boarded up or replaced with something weirdly nouveau, gleaming towers, and that new convention center. Still unchanged are the names of downtown’s strangely angled streets, laid out — so the story goes — by a couple of drunken city founders. To navigate the grid, one is advised to memorize an irreverent rhyme using something of a stutter: “Jesus Christ Made Seattle Under Protest” (Jefferson, James, Cherry, Columbia, Marion, Madison, Spring, Seneca, University, Union, Pike, Pine).

It’s unsettling to be a tourist in a place that once was yours. Unsettling and yet okay. The nouveau may be better, maybe not. The future will figure it out. I no longer require doses of urban energy. I fill up each morning with the silence of my neighbor — a slow-flowing river — and the occasional quack of a duck, chirp of a bird. It’s all the energy I require.

You must be logged in to post a comment.