A free concert at Benaroya, Seattle’s premier performance venue. Knowing there’d be a crowd, my neighbor and I left plenty early for our walk to the event commemorating International Holocaust Remembrance Day (Jan. 27). We ended up with time to visit the Garden of Remembrance, which stretches along the west side of Benaroya.

More than eight thousand names of Washington State citizens who died in service to our country since 1941 are etched into the granite walls. Names include people who served in World War II, the Korean War, Vietnam, Gulf War and continuing through post-9/11. I immediately went to the Vietnam section and gently placed my fingertips on the name Keith Henrickson, a high school friend. It’s a gesture I’ve made before, first at the Vietnam memorial wall in Washington, D.C., and again when a traveling replica of that wall visited the Colville Indian Reservation, near my former home.

I thought about how I’ve lived fifty-five years longer than Keith, who was killed at age twenty-four in Quang Tri province. Yet his name, etched in granite, is an enduring presence that will last long after I’m gone. His and all the other names are an ongoing witness to the tragedies of war.

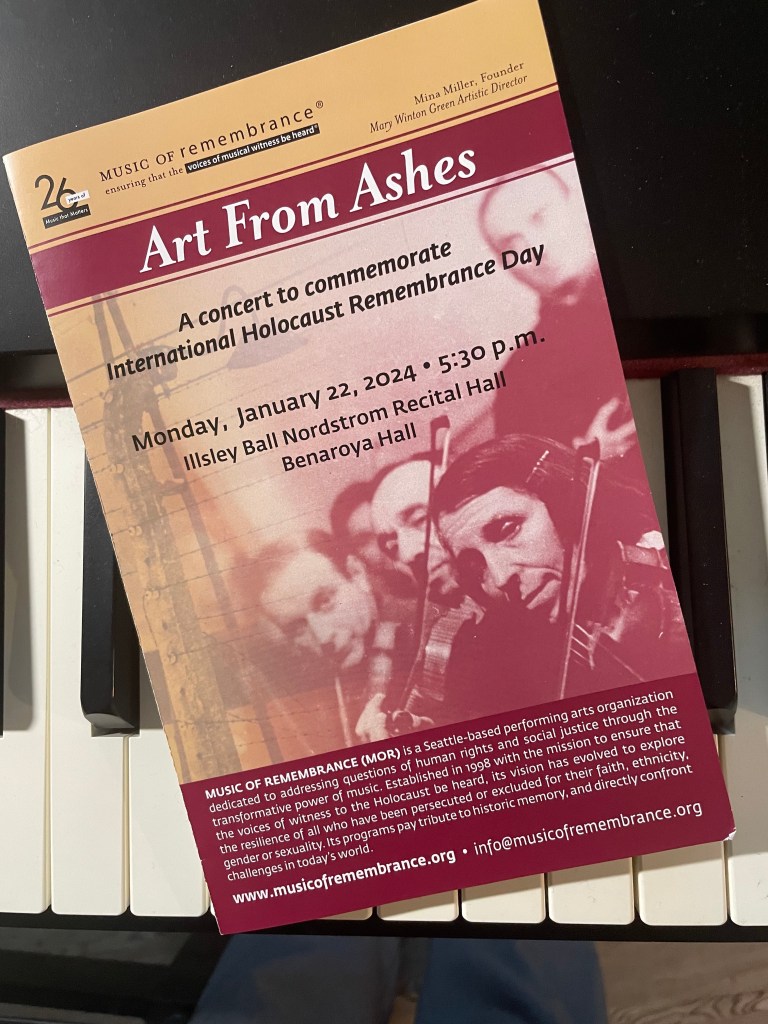

Scattered raindrops accented my somber mood as we left the garden and entered the hall. The concert was presented by Music of Remembrance, a nonprofit organization that addresses issues of human rights and social justice through music. As I read the program, I readied myself to shed tears. Many of the pieces were attributed to poets and composers who perished in Nazi concentration camps.

I wondered about the quartet of pre- and teen siblings a couple rows ahead of me. Would they “get” it? They were jostling and elbowing each other in normal but disruptive ways. Their parents were seated like bookends with their offspring between. I hoped that Mom and Dad could/would keep the kids under control. Then, just as the lights were dimming, I heard the rustle of newcomers settling into the row directly behind us. I looked around to spot a young couple with two children, ages about three and one.

I immediately flashed back to a free, noon organ concert that my late husband and I attended decades ago at the Mormon Tabernacle in Salt Lake City. The place was packed with tourists. The organist began with a brief welcome and firm direction: “If your child becomes disruptive or makes any kind of noise, do not hesitate to remove them immediately.” I don’t recall the organist’s name, but I have silently evoked his instruction whenever concerts get disrupted by crying or rambunctious children.

The audience dropped into silence for the opening “Intermezzo for Strings,” a floating, ethereal piece performed by The University of Washington Chamber Orchestra. The Jewish composer, Franz Schreker, had been forced from his position as director of an important music conservatory. But he cheated the Nazis out of killing him by dying after a stroke in 1933.

The program continued, the youngsters in front of me quietly absorbed, the baby behind uttering only an occasional coo that was quickly muffled by her mother. About halfway through came a duet for violin and cello by Gideon Klein, a brilliant musicology student who died in the Fürstengrube camp at age twenty-two. The mournful, longing music ends suddenly mid-phrase, as did Klein’s incomplete life. In the silence that followed, before the audience could gather itself to applaud, the baby let out an anguished wail. Her cry said far more than our applause. Nonetheless, Mom gathered her up and exited the hall.

She missed the grand finale, “Farewell, Auschwitz,” a defiantly jubilant piece commissioned by Music of Remembrance. It was performed by The Seattle Girls Choir and Northwest Boychoir, along with instrumentalists and adult soloists. I was heartened by the discipline and beauty of the young voices. They were learning in a powerful way about an historical truth that too many try to deny.

Upon leaving the hall, I spotted Mom and baby seated on a bench. I perched next to them, the baby giving me a bouncing grin as I told her mom, “I’m sorry you had to miss the end of the concert. She was so good for so long, and I’m glad you brought her. She has that music embedded in her soul now.” Just as I finished speaking, another woman approached.

“Good for you for bringing the children to the concert,” she said. “They’re never too young.”

Never too young — nor too old — to learn, to change, to grow, to remember.

You must be logged in to post a comment.