If you’re heading out on a cross-country road trip, your first stop should be at a beautiful place close to home. That way, when you discover you’ve forgotten something important, you can return for it without too much backtracking. More significant, no matter how exotic the sights on your journey, you’ll remember that home is beautiful, too.

My shakedown cruise for this year’s cross-country sojourn was a night at Bridgeport State Park on the Columbia River, just 45 minutes from my house. A friend and I spent the night in my camper van so we’d already have that drive under our belts, giving us 45 minutes more sleep before the 5:30 a.m. First Salmon ceremony at the adjacent Colville Tribes Fish Hatchery.

The park is beautiful: lush green lawns, plenty of space between camping sites, trees, birds, walking paths and views of the rugged cliffs that border Rufus Woods Lake, the reservoir behind Chief Joseph Dam.

But what caught my heart was the ceremony. An early morning sun highlighted cascades of water thundering over the dam, landing in a tumultuous spray. Prayers were sung in a language I don’t understand, yet the message of thanksgiving was as clear as mountain spring water. Elders spoke longingly of their fishing traditions before dams on the Columbia blocked fish migration. The massive concrete structure—“Chief Joe,” as the locals call it—loomed in the background as native fishermen stood on a steel platform, struggling to net that First Salmon. The scene was a pale imitation of the ancient fishery, yet it represented hope and determination.

This year’s ceremony was especially meaningful. The hatchery was promised when Grand Coulee Dam was constructed in the 1930s. That promise wasn’t kept until this century. The hatchery was completed in 2010. The tribe released its first ocean-bound smolts —1.8 million Chinooks — in 2013. Those are the fish returning this year. Sadly, there won’t be many of them. Tribal biologists forecast a seriously diminished spring chinook run, due to a variety of environmental issues.

Ultimately, the tribe plans to release 2.9 million smolts annually.

“Mother Nature always has something to say about that,” smiled one of the tribal scientists, adding confidently, “We’ll get it figured out.”

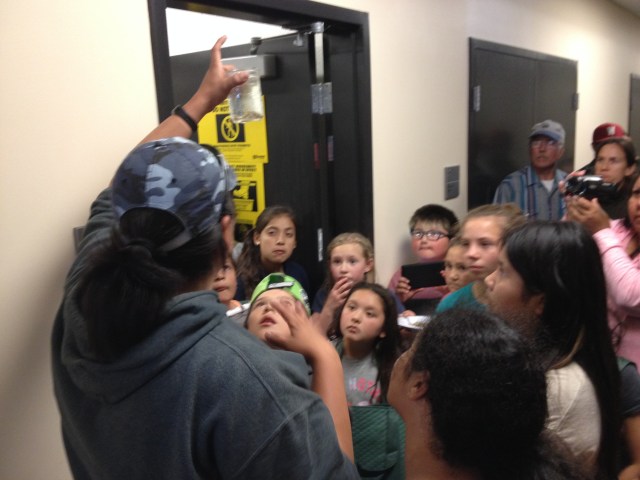

The First Salmon ceremony is deeply spiritual, also incorporating the science, culture, history and politics of the fishery. We listened to speakers as the fish was roasted on sticks over a fire. Then a small bite was given to each of us — about 150 people.

“It is our sacrament,” a tribal member said to me. Just as that mysterious connection with the divine is celebrated through the Christian sacrament of Holy Communion.

When the dams were built, it was not simply a food supply that was lost. Salmon nurtured the soul of a culture that had thrived for thousands of years. That soul still flickers with life, just as this year’s First Salmon thrashed in the net before giving its life for the gathered people.

You must be logged in to post a comment.