Let’s call it pro-active aging: making the big decisions for ourselves before the inevitability of time and age compel others to make them for us. It’s why I’m selling my car, my home, most of my possessions, and moving 250 miles to Horizon House, a retirement community in the heart of Seattle.

It’s a “Continuing Care Retirement Community” or CCRC. There are about 1,900 CCRCs nationwide, says AARP, offering “a long-term care option for older people who want to stay in the same place through different phases of the aging process.”

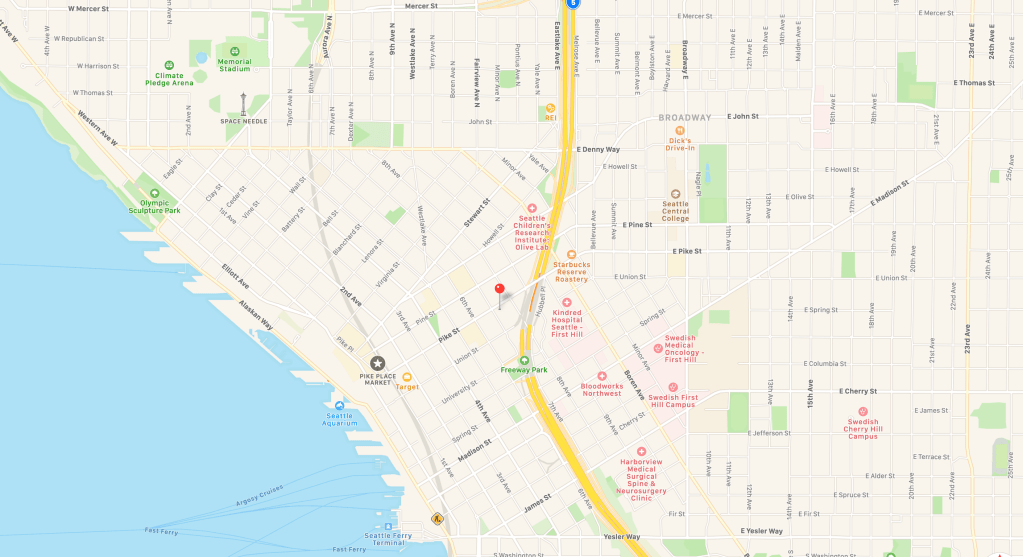

At seventy-nine, I consider myself barely into Phase One of “the aging process.” This is a pretty typical age for moving into a CCRC, I’m told. Residents are still young and agile enough to enjoy the long list of amenities: gym and swimming pool, hobby and entertainment rooms, library, special events, lectures, etc. I’ll be able to walk to theaters, restaurants, museums. Routine health services are provided in-house. Nearby are several of Seattle’s primary health care facilities. No more overnight, 200-mile round trips from my rural home for ordinary procedures like cataract surgery.

I’ll reduce my carbon footprint as I turn to public transportation and squeeze into 340 square feet of a studio apartment. Is this easy? Absolutely not. Is it an adventure? Absolutely.

Not everyone around my age or in my situation would choose the same. I hope all of us, as we age, are given the freedom and dignity to make our own choices. Sharing this decision with friends and neighbors has been the toughest part. Most agree it’s a good choice, but they (and I) lament my soon-to-be absence from the Okanogan Valley, my home for more than half my life.

I’ll leave behind people I admire and cherish. I’ll leave behind the Okanogan River, which every day inspires me with its steady flow and diverse wildlife. I also must leave behind Tawny, my eight-year-old rescue dog of many breeds. He’s a charmer who deserves better than confinement in a high-rise city apartment — even if he were allowed there, which he’s not.

Still, it is possible to thrive in a season of transition. With only a few months left here, my default mode is to savor. First thing in the morning, I step outside to savor river-scented air and murmuring ducks. At bedtime I step out again to say goodnight to a waxing moon and its reflected path across the glassy water.

I savor each and every encounter with friends. A quick “hi” in the post office lobby. A meandering conversation over a game of cards. Deep discussion during a three-hour lunch at the Mexican restaurant while the waiter patiently, continually refreshes our coffee.

I savor all the ordinary, everydayness of small-town living, like making an early Sunday morning run to the grocery store, where the only other soul is the owner, who rings up my forgotten carton of milk.

I savor the thought of another new season in my life while maintaining the illusion that I’m in charge of me. I’m sure there’ll be sunny days and a few gloomy hours to come. I intend to share those joys and sorrows, and so, dear reader, please savor this adventure with me.

You must be logged in to post a comment.