The stretch of Interstate 5 between Seattle and Tacoma is long familiar to me. The man-made landmarks have changed over the decades I’ve driven this route. But the Creator-made landmark, the mountain that we inappropriately call Rainier,* is constant, standing vigil over this vast and turbulent Puget Sound territory.

“You’re home,” The Mountain said to me as I drove a steady 60 mph (being steadily passed by fretful Puget Sounders). “I’m home,” I murmured, startled. Instantly the next thought landed: “Did I just dream the past forty-four years of my life?” Did I out-Ripple Van Winkle? Was I picked up by some tornado and set down in a land of Oz, aka the Okanogan Valley? Did I just spend more than half my life in a place that doesn’t really exist? For surely, the Okanogan — its land and its people — are too good to be true.

The state of Washington is really two states. Of mind. Some people call the massive north-south mountain range that divides the state the “Cascade Curtain,” recalling the infamous Red Curtain of the Cold War. Western Washington is perceived as urban, densely populated, gridlocked and expensive. East is rural, agricultural, with wide-open spaces that are getting expensive. West is the “wet” side, East dry.

In my thirties, during a stint as Washington state editor for the Associated Press, I learned to love the state’s diversity of people, landscape, culture, and ecology. It felt — and still feels — like this rich state has something for everyone.

Still, I was content on the west side until, at age thirty-five, I got swept eastward by a tornado named John E. Andrist and dropped into the Okanogan. It’s a land shaped by glaciers and a people shaped by the land. Rugged. Solid. Nurturing. Bountiful. Beautiful. The next fourteen years I lived my dream, sharing the fun and frustration of publishing the best doggone weekly community newspaper we could. The dream was rudely interrupted by John’s stroke and another fourteen years devoted to the frustration and fulfillment of caregiving.

If I’d follow the every-fourteen-year pattern, I would’ve moved two years ago. I couldn’t pull myself from my cozy home by the Okanogan River. I couldn’t pull away from the land nor — most of all — from the people who are so deeply rooted in that land.

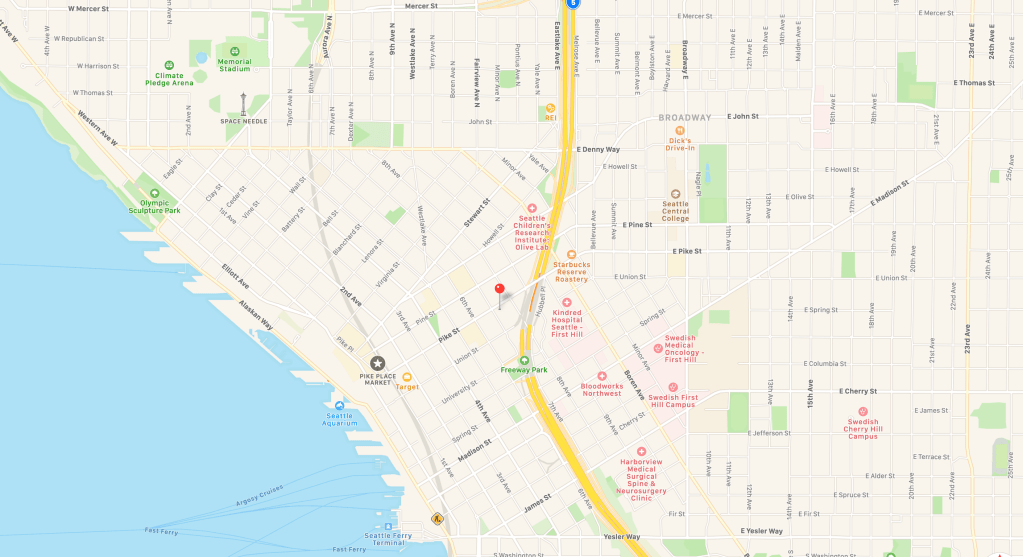

Somehow, a few weeks ago, I yanked myself away. Now I’m sitting in a thirteenth floor apartment on Seattle’s First Hill, gazing at the city skyline and mostly at the sky. I’m no longer soaking up the river’s flowing energy, but I’m energized by the equally constant flow of clouds, birds, planes. Every once in a while my gaze is distracted by the stream of tiny vehicles and pedestrians below.

My computer isn’t convinced that this is our new reality. No matter how many times I update the settings, it insists on alerting me to weather in the Okanogan. Please, all of you who are technologically more adept than I, do NOT by any means send instructions on how to “correct” the computer. There’s that saying: home is where the heart is. The reverse is also true: my heart is where my home is. The computer reminds me that my heart still beats to the rhythm of the Okanogan, and it always will.

*Indigenous people had perfectly lovely names for Washington state’s signature mountain before the Europeans arrived. One was pronounced something like “Taquoma” and meant “mother of all waters.” The name “Rainier” stuck after Captain George Vancouver named it for his buddy, an admiral in the British Navy who never saw the mountain and fought against Americans in the Revolutionary War. Efforts to rename the mountain haven’t gained much traction, but the name change of Alaska’s Mount McKinley to Mount Denali in 2015 may signal a change of attitudes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.