“Cast in concrete” is a metaphor for something permanent, unchangeable. And yet, “nothing is forever,” my late husband John once observed.

Cast aluminum, not concrete, was a favored medium for sculptor Richard Beyer. At least one time, however, he did make his mark in concrete. It was a fond gesture, a gift beyond value honoring John, me, and the community newspaper we published in Washington state’s spacious Okanogan County. John’s observation became all too true. Not even art cast in concrete is safe from willful destruction.

The Seattle Times recently published a retrospective of Beyer and his work. Reading it, I nearly drowned in a tsunami of memory and emotion. The piece by veteran journalist Erik Lacitis described Beyer as controversial and largely unrecognized. I have to agree. A recent show at the Seattle Art Museum celebrating contemporary West Coast artists omitted Beyer, even though there are more Richard Beyer public sculptures in Greater Seattle than by any other artist, Lacitis notes. That includes “Waiting for the Interurban” in the Fremont District, which after it was installed took on a life of its own. Many would claim it to be Seattle’s most popular piece of public art. Lacitis tallied more than ninety Beyer art works scattered throughout the Northwest and as far as Uzbekistan in Central Asia.

Beyer expressed his outsized humor in satirical creations that were met with consternation and adoration, fury and fun. He was either amused or indifferent when art snobs or critics spurned his folksy work. Since he died in 2012, his sculptures have not only endured but become even more endeared.

A Beyer fan long before we met, I was excited when he and his wife Margaret moved to Okanogan County in the late 1980s. I eagerly attended a show featuring some of Beyer’s smaller pieces at Sun Mountain resort in the Methow Valley. As I studied an eighteen-inch high, cast aluminum figure entitled, “Man Throwing Newspapers into Garbage Can,” I became aware of someone standing next to me. I looked up and instantly recognized Rich. My first words blurted to this man whose work I so admired were: “You could at least have him recycle them!”

Rich was momentarily taken aback before releasing his characteristic guffaw. We became friends, and I bought the sculpture for my husband. John proudly displayed it on the front counter of our newspaper office. Rich, who had so often been skewered in print, was no fan of newspapers. He made an exception in our case, frequently complimenting our paper’s brand of community journalism.

In late 1993, my husband suffered a brainstem stroke. Unable to speak, he was diagnosed as “Locked-In,” a syndrome described as a fully functioning brain locked inside a totally paralyzed body. Despite the gloomy medical prognosis, I was convinced John could and would recover. To accommodate John’s wheelchair, I had a ramp built to the front door of our newspaper office.

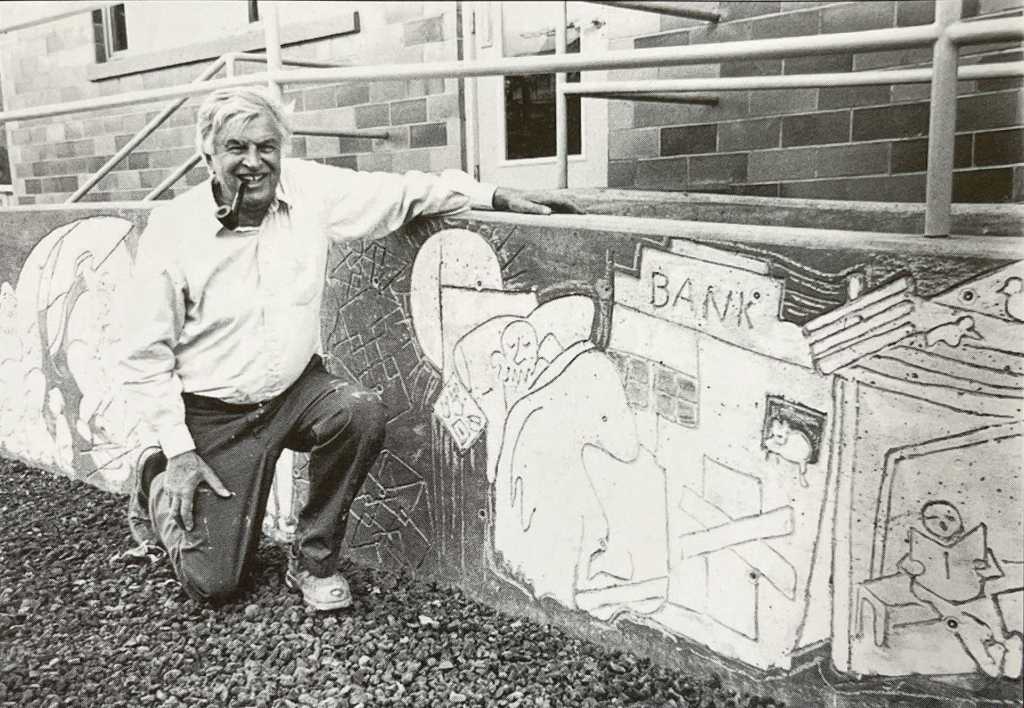

The contractor was Gary Headlee, also an artist and Rich’s friend. He convinced Rich to etch and paint a mural onto the side of our concrete ramp. Rich dreamed up a whimsical story that, as he worked, changed with every telling. He titled it “The Precious Jewel.”

By 1996, I had to face reality. Trying to do both John and my jobs, largely from home, while providing twenty-four/seven care for him, was not sustainable. We sold the paper, careful to put on a happy face in public. In private, I wept. I’d sold a chunk of my soul and pretty much all of my identity.

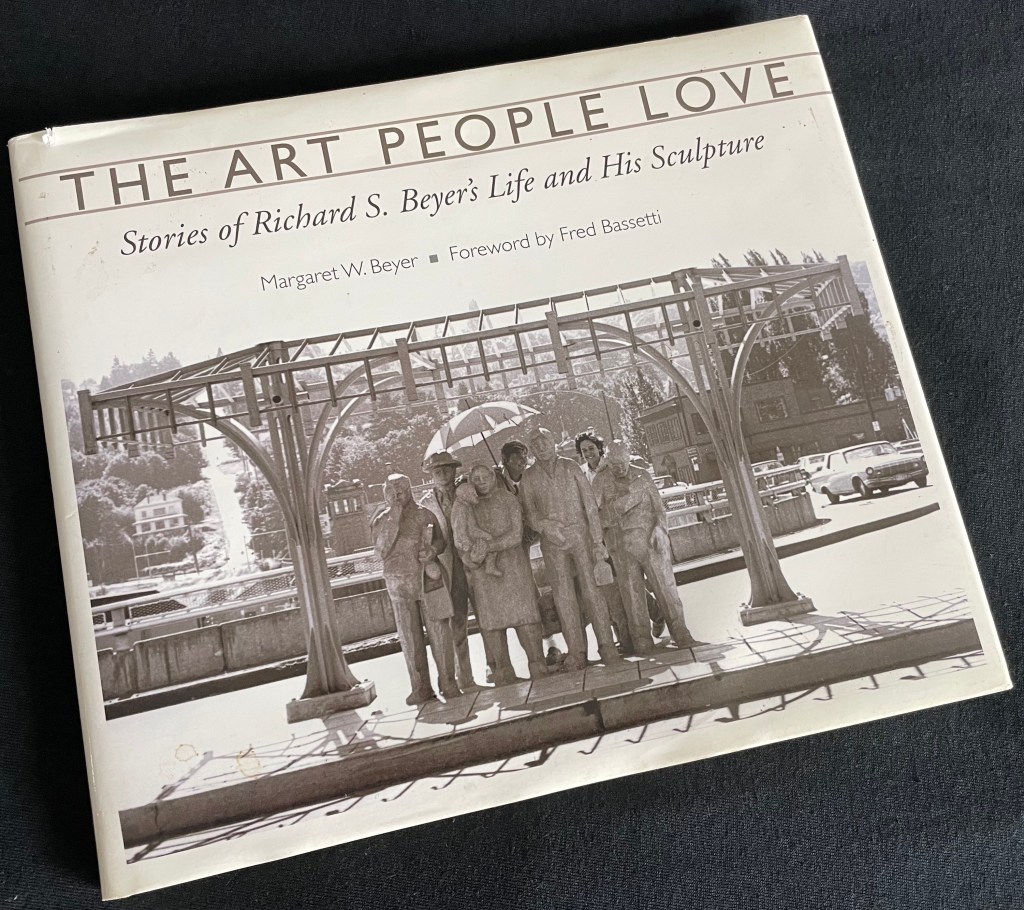

Not long after, Margaret got in touch with me. She wanted to write Rich’s biography and asked for my help. She arrived at our house with a shopping bag full of notes, photos, and a title for her imagined book: “The Art People Love.” I went to work on the opening chapters, but time was not on our side. I had too little of it, and Margaret wanted the book published ASAP. She ultimately retrieved the unfinished manuscript, the rest of her notes, completed the book, and found donors to fund its publication in 1999.

“Mary: you showed me the way!” she graciously wrote in my copy. One beautiful May morning in 2004, Rich called. Margaret was nearing the end of her journey with cancer. Would I come visit?

I’ve always described spring in the Okanogan as the five minutes when snowmelt colors our brown hills a delicate green. That day, throughout my forty-five minute drive to Margaret’s bedside, the green shone more brilliantly than I’d ever seen, before or since.

I don’t know if Margaret was aware of my presence. I prayed, seeking forgiveness for not having done more for her. She’d been the rock, the firm foundation that allowed Rich freedom to create. She was equally as brilliant and creative, yet self-effacing. I treasure a small watercolor that Rich gave to me. Margaret had painted it. I also treasure “Man Throwing Newspapers into Garbage Can,” which stands at my apartment door.

But “The Precious Jewel?” The new owners of the newspaper decided to remodel the building. The Beyer mural didn’t fit into their plans. They brought in heavy equipment, turning a work of art into a heap of rubble. I was shocked and horrified. Gary retrieved some of the larger chunks of brightly painted concrete and piled them next to a building he owned on Main Street. Every time I drove by, they reminded me that my dreams and expectations had also been shattered. Even the legacy of art I thought we were leaving to the community was destroyed.

After reading the Lacitis article, I had a sleepless night. Why, I wondered, had such a beautiful tribute left me so troubled? A hundred-or-so tosses and turns later I realized: some wounds never heal. We must tend to them, care for them and avoid infection. Bitterness will only contaminate ourselves and others.

The capacity to destroy is within us all. Some feel empowered by envy, greed or fear to rationalize acts of destruction. Others counter the darkness of destruction through love, creativity and compassion.

We are experiencing an epic era of destruction. Mouths agape, stunned, we daily witness attempts to demolish essential institutions — art, science, public education, and — this especially hurts — venomous attacks on freedom of speech and ethical journalism. We grieve as people’s lives are ruined. We gasp at the erasure of values we thought were cast in concrete in the U.S. Constitution. People are marching in the streets, yet in our hearts, how do we confront this darkness?

Spiritual writer Rabbi Brian Zachary Mayer recently offered advice in one of his emails: “Forgive and forget. And if you can’t, pick one.” I can forgive. I long ago forgave the destruction of “Precious Jewel.” Empathy for another paves the path toward forgiveness. Maybe I can forget the pile of concrete rubble, but no amount of heavy equipment can smash my memories of the artists’ generosity, joy, and love.

I realize now that those memories nurture a confidence that is cast in something more solid than concrete. It is a confidence in Martin Luther King Jr.’s “long arc” toward justice. It is a confidence to resist, to seek truth, perhaps even to hope. It is vital not to forget.

An old man tells a story:

A man mines the sky

and finds a beautiful blue gem.

Holding it to the light he sees the world anew,

in 4 dimensions

The governor is asleep,

The banks are closed,

Cattle have moons in their horns,

Children ride flying horses,

Angels fill the trees,

Rocks speak,

Coyotes dress in Wal-mart suits,

The snake pipes and the rabbits dance,

Fish and the wapato dance too.

He gives the stone to his wife to look through,

To see what he is seeing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.