Ordinarily, the last thing one wants to hear at a chamber music concert is a crying baby. But these are not ordinary times.

The Seattle Chamber Music Festival pre-concert performance would last only a half-hour. It would take longer than that to walk to Benaroya Hall and back. Still, a crisp, sunny afternoon beckoned and I needed to get away from the news. Especially news from Minneapolis, where I was born.

“It is a daily discipline to choose how much of the world’s darkness we touch and why,” wrote Debra Hall in her poem, “The Wrapping Ceremony.” An excerpt from the poem has been on my refrigerator door ever since it was published by We’Moon in 2023. The print-out has become wrinkled and faded because I refer to it, well, daily.

“We could be incandescent with righteous rage every second of every hour. Our collective grief could raise the sea level overnight,” the poem continues. Then, a few verses later, she advises: “It is joy too we are here to spend.”

Her inclusion of the three-letter word “too” is most important to me. The poet doesn’t suggest we disregard and deny our grief and rage. We can also — we are required — to make room for joy. That is our human condition.

A fellow human was fatally shot on the streets of Minneapolis. I recognize the street names. They were streets I walked along at age ten. My parents considered it safe for me to take a bus downtown, unaccompanied, to Saturday morning piano lessons.

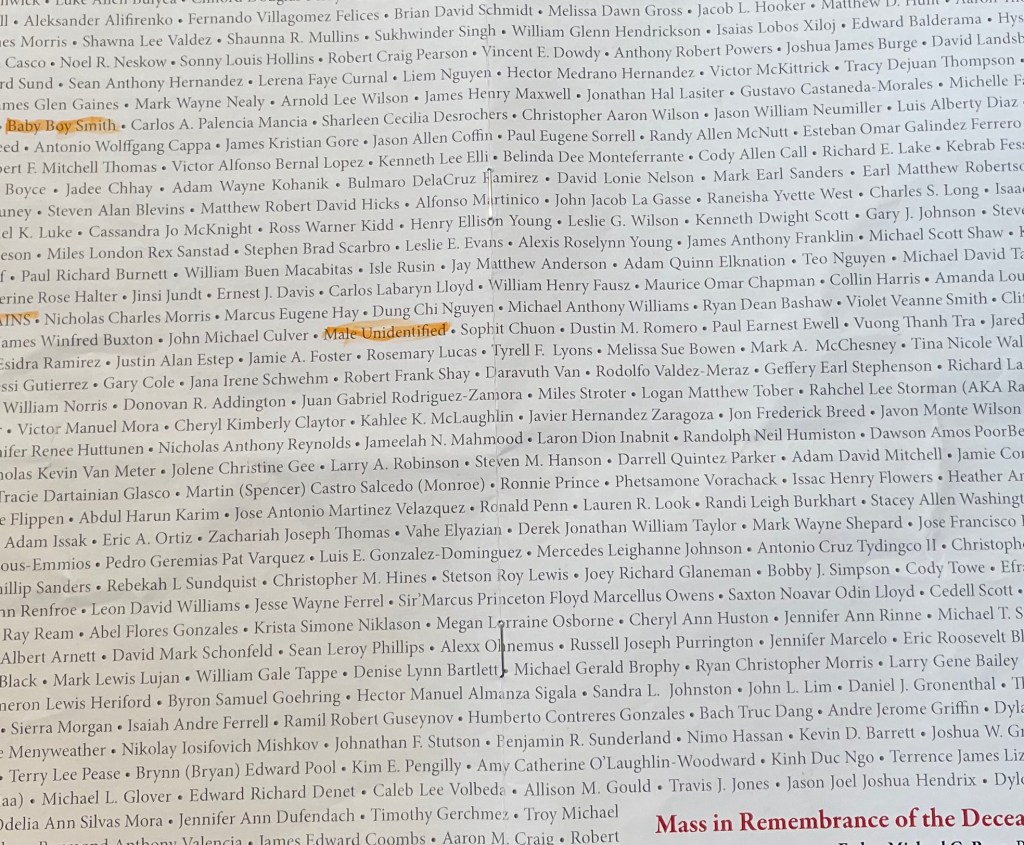

That was then. This is now. Each day the news gets darker. Headline: “Minneapolis Man Killed by Federal Agents Was Holding a Phone, Not a Gun”

It is a daily discipline …

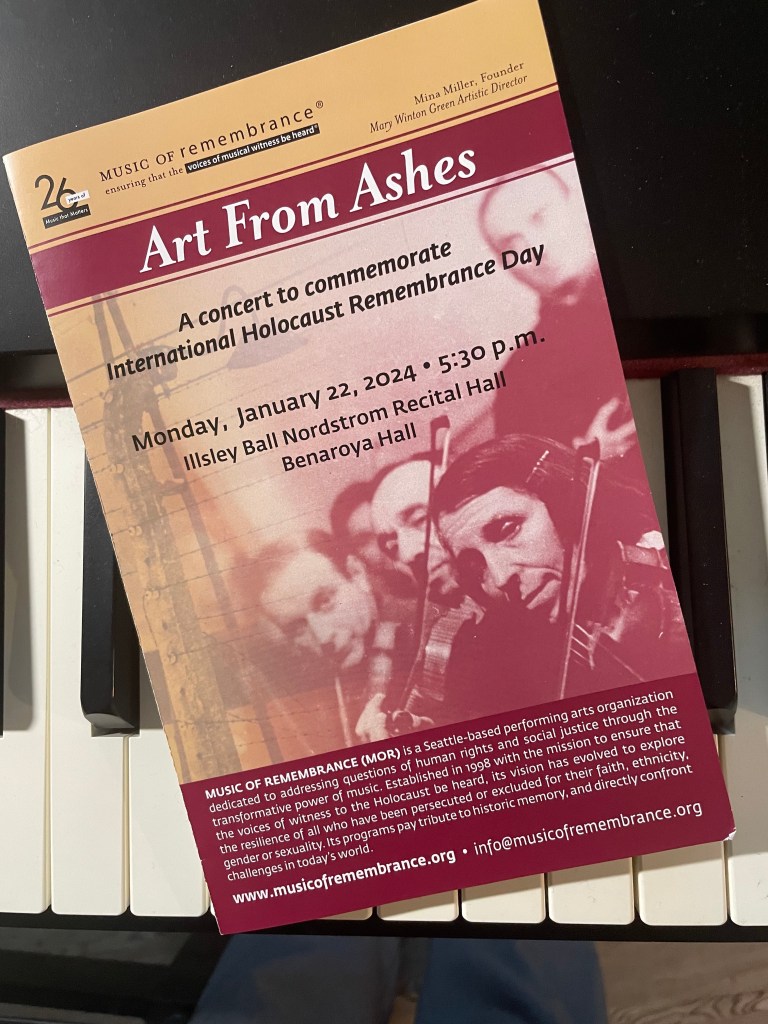

I closed my computer, donned a heavy jacket and headed for the concert hall. There were plenty of empty seats even though the concert that followed was sold out. Perhaps the pre-concert program was too weird for chamber music fans: a half-hour of improvisation by a cellist and percussionist.

I can’t remember the last time I’ve been so captivated and comforted by music. I’d heard Efe Baltacigil, a native of Turkey and Seattle Symphony principal cellist, play on other occasions. I knew he’d be good. Mari Yoshinaga, a Japanese native with a master’s degree from Yale, surrounded herself with a panoply of exotic instruments. I took a percussion class in college yet couldn’t begin to name all that she played.

The art of musical improvisation requires a mutuality, a confidence in the other musician that goes beyond words. That unspoken trust was apparent from the opening sounds and only intensified as the music continued. After some twenty minutes, the musicians took a breather. Yoshinaga announced that her child, not quite one year old, was in the audience with her husband. She would sing a song the baby particularly likes — not a lullaby but “My Grandfather’s Clock.” The song, composed in 1876, became popular in Japan in the 1960s as part of a children’s TV show. She sang softly, barely audible, accompanied only by a quiet rhythm instrument. When she completed the first round of the song, the cello joined, hushed and gentle.

That’s when the baby began to cry. Not a wail. Neither a coo. Something in-between. Something, oh, longing.

Ordinarily, an audience of mostly white-haired classical music lovers, might have stiffened with irritation. But in this moment, a silent sigh rippled through the hall, a soft murmur of joy. Baltacigil stopped his bow, signaling Yoshinaga to continue singing. The babe gave a few more cries, the kind you hear when an infant is winding down, reassured by a gently rocking embrace. Eventually the music again got lively. The baby was silent, sleeping perhaps, even through boisterous applause when the performance ended.

When I got home, I discovered I’d missed a call from a friend in Wisconsin. Mother of three young children, she wanted my perspective on events, especially in Minneapolis. What is happening there is too close to my heart. I have no perspective. What I want to say to her is, hug your children. Hold them close. Sing to them.

You must be logged in to post a comment.