“Take the steps on your right,” GPS instructed via my phone. I looked at the steps with skepticism bordering on apprehension. They dissolved into a steeply declining, forested urban trail.

It should not have been a concern. I’ve hiked in the Glacier Peak and Pasayten wildernesses, the Cascade Crest Trail (parts thereof), and the coastal trail of Wales (parts thereof). I walk at least a couple miles daily. This time, though, I was on a scouting mission. A friend, who was planning to visit with her eighty-something mother, texted she’d found an Airbnb just a block from my apartment. I checked the address and thought, “Yeah, just a block as the crow flies, maybe.”

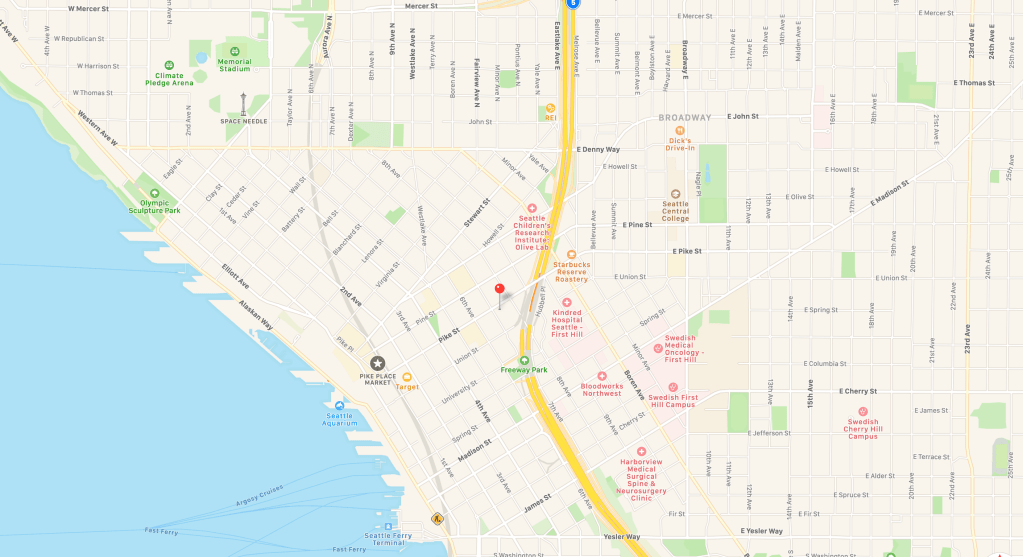

In Seattle, it can be difficult to get from Point A to Point B without circling via points Q through Z. Look at a map of Seattle’s core, and it has all the puzzling disjointedness of an Escher print. There are a couple of reasons for this. Seattle’s founders built on a series of hills, some quite steep. My roundtrip walk to the grocery store is only a mile, but no matter which route I take, it’s uphill both coming and going.

The real confusion, though, evolved when three early developers couldn’t agree on which direction the streets should follow: north-and-south, as the compass would dictate, or northwest-to-southeast, following the Puget Sound shoreline. Each went his own way so that when streets ultimately meet, they zig or zag, sometimes even criss-cross. It’s not unusual for streets to intersect at an acute rather than the usual right angle. Seattle architects have excelled in designing buildings that come to a point.

As if all that weren’t sufficiently problematic, interstate freeway construction in the 1960s plowed through Seattle’s core, bisecting the city and blocking streets that long had been thoroughfares between neighborhoods. A “lid” over a small portion of the freeway affords some access via Freeway Park. The retirement complex I live in abuts the park, but even pathways in the park wind and wander. As far as I can tell, GPS has yet to figure out those trails.

All of which led to my scouting venture. My friend’s Airbnb was indeed just a block from my apartment complex loading dock. Visitors are not welcome there. The front door is still another block beyond. Since visitors can’t go through the buildings, they pretty much reach the main entry via points Q and Z.

I’d put my friend’s Airbnb address into my phone as I exited my apartment building. GPS directed me along a side street to the top of the before-mentioned trail, where I found squalid remains of a campsite, apparently vacated by homeless persons. The trail was paved, but the wooden handrail was covered with graffiti and appeared less than sturdy.

I headed downward, gingerly stepping over broken glass, noting an abandoned grocery cart in the bushes. Bulbs were pushing up initial green spikes of spring flowers through last fall’s dead leaves. At some point, this must have been a lovely urban pathway. Now, I texted my friend, it was more of an urban jungle.

“Hmmm, what do you mean an urban jungle?” she texted back. “Is it not safe?”

“Back-alley aura,” I answered.

My friend is a determined, undaunted world traveler. She found another route via a stable staircase. From there she cajoled her mother into climbing two blocks up a rigorously steep sidewalk. They could’ve driven, but with one-way and dead-end streets, multiple construction detours, and parking issues, it would’ve taken much longer.

Ah, wilderness. Right here in my urban backyard.

You must be logged in to post a comment.