These two were awkward to photograph. I purposely have them in a corner so they can gaze at each other as “The Flute Player” sends his music flying like birds for “The Listener” to hear.

The prints are by Laura Woolschlager, a longtime friend, who showed them at a benefit art exhibit my husband and I attended in late November, 1993. John and I had already agreed beforehand that we would not buy anything. Underline not buy. Underline anything. We already had more art than walls on which to hang it, including several paintings by Laura. When I expressed delight in these two prints, John—behind my back—quietly signaled to Laura that he would buy them. Presumably as a Christmas gift for me.

Days later he suffered the stroke that would leave him totally paralyzed and unable to speak for the final fourteen years of his life. By Christmas, he was in a rehab facility in Seattle, and I was at his side. A carefully wrapped package arrived from Laura containing the two prints and a long-sleeved cashmere sweater. She refused payment for the prints and suggested that when I wore the sweater, it should feel like John embracing me.

These prints are meaningful not only because of Laura’s generosity, but because they were harbingers of what was to come in our lives. The two lovers are separated. If Laura had placed them in a single painting, the idea would have lost its power. The flutist’s music escapes beyond the frame, beyond boundaries, as birds flying to his lover, the listener.

When someone becomes caregiver to a spouse, there is a new frame of reference, a separation of sorts, dictated by new responsibilities. What was once a shared landscape becomes two islands, individually afloat. Yet love itself deepens and soars, escaping all boundaries, flying free as birds, connecting across the divide.

(To celebrate my 75th birthday this month, I’m posting daily stories about the stuff I’ve acquired over a lifetime and can’t let go of. I invite you to consider and possibly share the stories that make you treasure your own stuff.)

I rarely wear T-shirts for the same reason I rarely take selfies: I’m rarely happy with how they look. Nonetheless, I have three of these shirts tucked away in a drawer. Maybe, just maybe, I could have a reason to wear them again someday.

I rarely wear T-shirts for the same reason I rarely take selfies: I’m rarely happy with how they look. Nonetheless, I have three of these shirts tucked away in a drawer. Maybe, just maybe, I could have a reason to wear them again someday. I played flute and piccolo; my husband played baritone horn. The band had a wide-ranging repertoire. Favorites were “I Love To Go A-wandering,” “Yankee Doodle Dandy,” and “The Stripper.” During the latter, one of the kazoo players would unleash a cascade of bubbles from an ornate bubble blower.

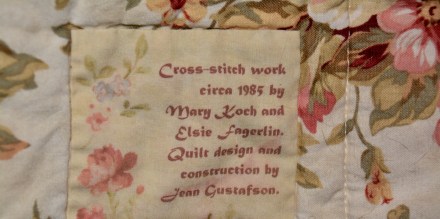

I played flute and piccolo; my husband played baritone horn. The band had a wide-ranging repertoire. Favorites were “I Love To Go A-wandering,” “Yankee Doodle Dandy,” and “The Stripper.” During the latter, one of the kazoo players would unleash a cascade of bubbles from an ornate bubble blower. “Mary gets everything!” my brother Mark teasingly chided our parents as they were slowly downsizing, distributing items among family members. Not that our parents had heirlooms of monetary value. If we wanted anything of theirs it was purely for sentiment.

“Mary gets everything!” my brother Mark teasingly chided our parents as they were slowly downsizing, distributing items among family members. Not that our parents had heirlooms of monetary value. If we wanted anything of theirs it was purely for sentiment.

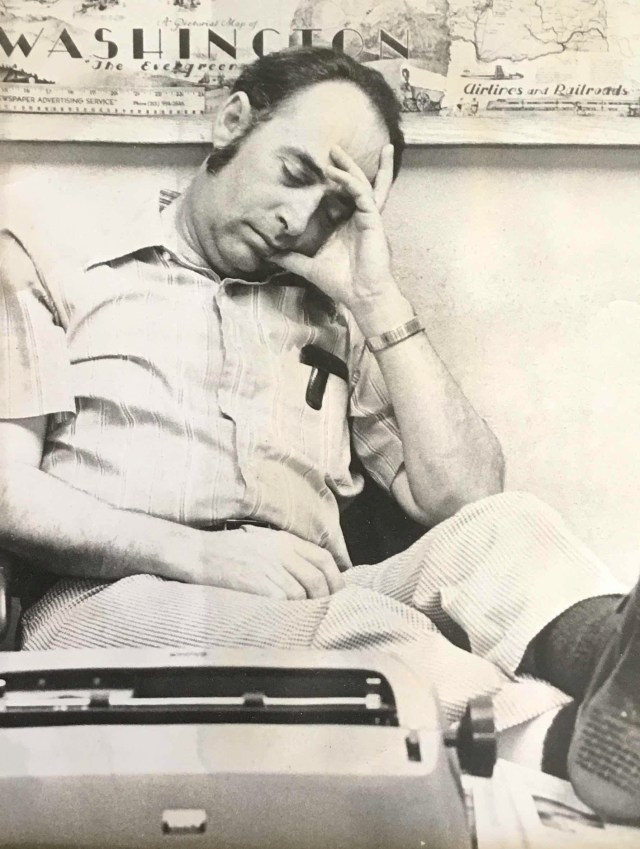

This little desk, just five-feet tall, has followed me around all my life. My mother told me it was made by her great-grandfather (photographed below with his wife). It must be at least 150 years old, or twice my age. Neither of my parents used it as a desk—it wasn’t sturdy enough to hold Mother’s typewriter, and my six-foot-plus dad couldn’t possibly fit his legs under the fold-down writing table. It was just an odd piece of furniture that got stuck in any available corner until ultimately it landed in my childhood bedroom.

This little desk, just five-feet tall, has followed me around all my life. My mother told me it was made by her great-grandfather (photographed below with his wife). It must be at least 150 years old, or twice my age. Neither of my parents used it as a desk—it wasn’t sturdy enough to hold Mother’s typewriter, and my six-foot-plus dad couldn’t possibly fit his legs under the fold-down writing table. It was just an odd piece of furniture that got stuck in any available corner until ultimately it landed in my childhood bedroom.

Like this little weeping cherry tree—a wedding anniversary gift from my parents to my husband and me. I’m not sure which anniversary it was, but I couldn’t leave the tree behind when I moved. I had it dug up from the old yard and replanted next to my new-to-me patio. It survived the transplant and is blessing me this May Day with a full bloom, a vibrant memorial to the three most important people in my life.

Like this little weeping cherry tree—a wedding anniversary gift from my parents to my husband and me. I’m not sure which anniversary it was, but I couldn’t leave the tree behind when I moved. I had it dug up from the old yard and replanted next to my new-to-me patio. It survived the transplant and is blessing me this May Day with a full bloom, a vibrant memorial to the three most important people in my life.

You must be logged in to post a comment.